County’s high C-section rate sparks questions

Published 6:25 am Thursday, July 23, 2015

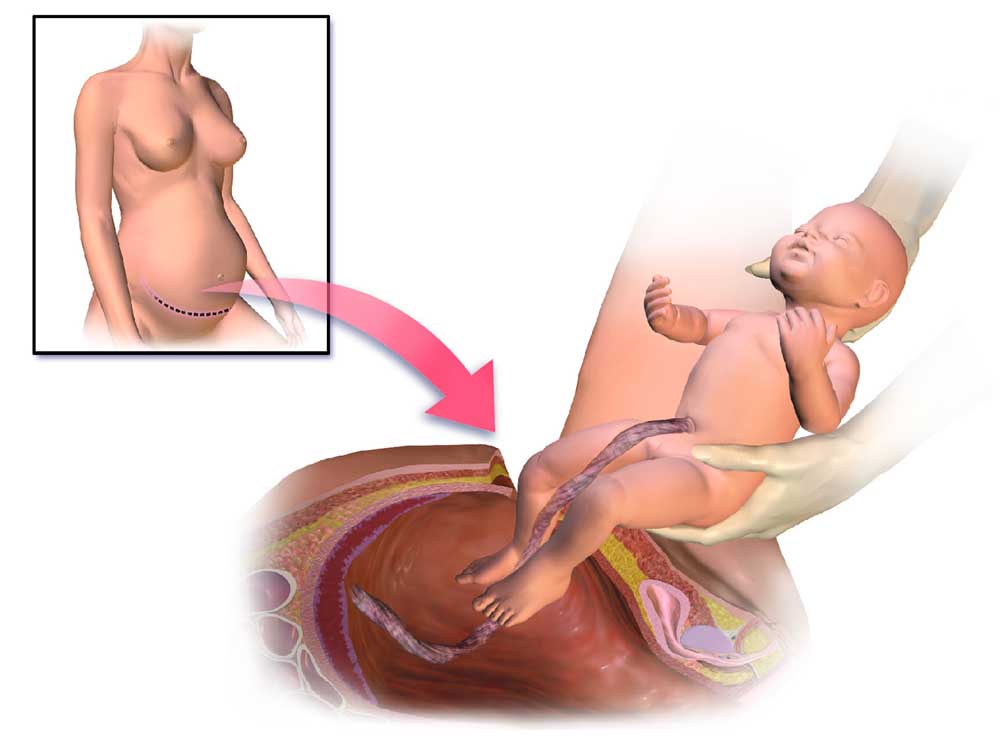

- This is an illustration of a cesarean section.

About a third of Clatsop County babies were delivered through cesarean sections this year through March. That is roughly twice the amount recommended by the World Health Organization.

From 2008 to 2014, of the more than 3,200 births countywide, about 29.3 percent were deliveries via cesareans. Vaginal births — including vaginal births after C-sections and home births — accounted for the other 70 percent, according to data from the Oregon Health Authority.

During those years, Columbia Memorial Hospital’s C-section rate ranged from a high of 34 percent in 2011 to a low of 27.59 percent in 2010. At Providence Seaside Hospital,the rate ranged from a high of 30.46 percent in 2008 to a low of 23 percent in 2013.

However, the average cesarean birth rate across Oregon and the United States during the past few years also has hovered well above the WHO recommendation of 10 to 15 percent. In 2014, the state’s overall C-section rate, according to data from OHA, was 27.42 percent, with the number varying significantly from county to county. In the nation, the rate was 32.7 percent in 2013, according to the most recent finalized data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

These numbers have people and organizations, including the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, questioning why the cesarean birth rate has jumped during the past few decades and what can be done to safely lower it to the benefit of women, who often experience longer recovery periods, a increased likelihood of complications in future pregnancies and other disadvantages after the surgery.

Cesareans can be life-saving procedures in some cases, but the WHO recommendation for the optimal C-section rate is important. It indicates that among health providers who have a rate higher than approximately 10 to 15 percent, there is no evidence to support that it is beneficial for either mothers or infants, according to Dr. Aaron Caughey, who is chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and associate dean for women’s health research and policy at the Oregon Health and Science University.

Maybe the high rate “is preventing bad things from happening, but we don’t really have any evidence to support that,” he said, which leads to suspicion there are thousands of babies being born through C-sections who don’t need to be.

When sorting through the factors contributing to high cesarean rates, the primary one seems to be pressure from the medical profession’s lawyers, Caughey said.

As of 2011, according to the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, more than 90 percent of OB-GYNs had been sued for malpractice at least once during their career, with an average of 2.7 claims per ob-gyn. Claims related to a neurologically impaired infant made up 30.5 percent of the obstetric claims, and of those, 49 percent were closed with some payment made to the plaintiff, “either settled with payment, closed by way of jury or court award, or closed through some other dispute-resolution mechanism,” the association states. The average payment for claims involving a neurologically impaired infant was $1,155,222

Even years down the road, if an infant or child’s neurological issues can be linked to their perinatal care or method of delivery, a doctor or hospital can be sued. It is much less likely a woman can or will sue because she had a C-section.

“It just doesn’t happen,” Caughey said. “People don’t get sued for doing C-sections; they get sued for not doing C-sections.”

As a response to the risk of liability claims and because of insurance costs and availability, doctors began making changes to their practice, including decreasing the number of high-risk obstetric patients, no longer offering or performing vaginal births after C-sections — referred to as VBACs —and increasing the number of cesarean deliveries, among others, according to the OB-GYN group.

Cesareans have become “very, very safe” to perform, which can lead to some doctors opting for that route sooner, rather than later, when complications arise to prevent potential infant injuries and decrease liability, Caughey said.

The pressure from liability is often not predominantly economic, Caughey said. Doctors purchase insurance for the sake of being financially covered in such instances. Rather than an economic cost, it’s “the act of being sued or having people around you being sued,” Caughey said. Most doctors enter medicine “because they thought they could make a difference in people’s lives,” he said. To be dragged through the court system, negatively labeled and personally blamed for something bad happening — “that’s pretty demoralizing,” Caughey said.

“It’s probably one of the strongest negative outcomes a physician can experience,” he added.

As for other economic considerations, Caughey said, “there is a lot of misunderstanding about how hospitals and physicians are paid.”

C-sections are more costly for patients. Doctors, however, do not make significantly more money from a C-section than a vaginal delivery. Hospitals also tend to lose money from the “birth business” in general, Caughey said. The one area hospitals make money through births is from charges relating to care for the newborns, who along with the mothers, are not discharged for a few days after a C-section. Also, if complications led to the C-section that may indicate the infant or mother needs further postpartum care, which chalks up more hospital charges.

“Safe Prevention of the Primary Cesarean Delivery,” a research paper developed by the OB-GYN association and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine in 2014, suggested alternative causes behind the increasing cesarean rate could be “modifiable factors,” such as “patient preferences and practice variation among hospitals, systems and health care providers.” Research has found maternal characteristics — such as age, weight and ethnicity — do not account fully for the increase in the C-section rate or its regional variations, the paper stated.

Columbia Memorial Hospital Community Outreach Manager Paul Mitchell said the hospital was part of the national Partnership for Patients initiative through the Oregon Association of Hospitals and Health Systems, which started in February 2013 and went through 2014. The initiative was aimed toward reducing patient harm by 40 percent and readmissions by 20 percent. The initiative had 10 focus areas, including birth-related injury to babies, Mitchell said.

Data from Oregon Health Authority shows the hospital’s C-section rate increased from 2013 to 2014.

Mitchell said he believes the hospital has seen a decrease in its C-section rate.

“The hospital has reduced early elective deliveries by developing criteria for determining when delivering a baby before 39 weeks of gestation is medically warranted and educating patients on the benefits of allowing babies to gestate,” Mitchell said.

At Providence Seaside Hospital, C-sections “are performed for many indications/reasons that may occur during pregnancy or labor, including the position of the baby and arrest of labor,” Public Affairs Manager Paulette McCoy said. “C-sections can be scheduled procedures or unscheduled during the hospitalization, due to events that occur in labor.”

Providence Seaside does not have a high-risk birthing facility, but collaborates with Providence St. Vincent and Northwest Perinatal Center for high-risk patients, McCoy said. CMH does offer care for women with high-risk pregnancies as part of its mission to provide care close to home, Mitchell said.

Mitchell and McCoy did not provide information on their hospitals’ liability management frameworks.

With cesarean birth rates around the nation mostly at more than double the World Health Organization’s recommended percentage, what are the other alternatives? What are the options for assisted child birth and the pros and cons?

Midwives and doulas provide a different role than hospitals in the birth process, but “everybody wants to provide good care; that’s the bottom line,” said Jennifer Childress of Nehalem. Childress, a certified professional midwife, has been in practice along the coast from Astoria to Tillamook since 2010, and has attended births for about 14 years.

Midwifery is targeted toward low-risk patients, which helps the profession have an overall lower C-section rate — or, rather, rate of transport to a hospital for a C-section to be performed, since midwives can’t do the surgery. Licensed midwives must ascribe to risk-assessment-practice standards addressed in the Oregon Administrative Rules, which state, “Licensees must assess the appropriateness of an out-of-hospital birth taking into account the health and condition of the mother and baby according to the following absolute and non-absolute risk criteria.” If the mother or baby presents with any absolute risk criteria, they are precluded from out-of-hospital births and midwives have to transfer care to a licensed physician.

Throughout her years of experience, Childress has successfully conducted vaginal, home-birth deliveries for a majority of her patients, which mirrors national statistics.

In a study of roughly 17,000 women conducted from 2004-09, published January 2014, the Midwives Alliance of North America found that for planned home births with a midwife in attendance: The rate of normal physiologic birth was more than 93 percent; the cesarean rate was 5.2 percent; 87 percent of women with a previous cesarean delivered their newborns vaginally; and of the 10.9 percent of women who transferred to a hospital during labor, the majority changed locations for nonemergent reasons. Also, the study found a very low rate of interventions without an increased risk to mothers and babies.

Besides the fact midwives are dealing with more low-risk patients than hospitals — which significantly complicates direct comparisons — trends also exist within the practice that could contribute to fewer midwives’ patients needing C-sections. A lot of midwives take a different approach to pregnant patients.

With fewer patients — Childress estimates she will have about a dozen this year — they often can spend more time with expecting mothers during prenatal visits. The focus of prenatal care is education, Childress said, adding, “We really focus on informed choice rather than informed consent” by presenting “patients with a whole range of options.”

“We realize that spending time in the prenatal period really assists in the end result,” she said.

During labor and delivery, midwives are protective of their patients and try to create a safe place for them, Childress said. Doing so helps the women’s own hormones guide the process, which can lead to the need for fewer external interventions.

Not to say midwives don’t use interventions, but they tend toward natural strategies. “Water is our home-birth epidural,” Childress said. That is partly because midwives are limited in what they can do medically, but also because of the profession’s dominant philosophy that birth is a natural process, not a medical procedure.

With midwives, birth “is treated like the most natural thing in the world, because it is,” Seaside doula Katie Mendoza said.

Rather than ascribing to a strict set of guidelines about what is normal for a birth, which makes deviations seem alarming, many in the home-birth business broaden the definition to include other “versions of normal,” said Priscilla Fairall, a local doula or nonmedical birth companion.

What she and Mendoza fear is happening at the hospital level is the institutions have started relying on early interventions, which sometimes lead to a cascade of further interventions.

Childress agreed that can be problematic.

“You start one intervention, and they just lead to one right after the other,” she said.

Childress said she believes medical professionals can avoid problems “by understanding how birth works.” She advocates patience and encourages women to do most of their labor at home where they can rest, because once they are in a hospital setting, “it’s often hard to relax in that situation,” she said.

Mendoza feels many things could be improved at the local hospitals when it comes to infant deliveries.

“All the hospital births I’ve gone to have not been great,” Mendoza said. “The celebration has not been there.”

Melissa Van Horn, who had her only child at Columbia Memorial several years ago and experienced severe complications, said “sterile” is the word she would use.

“There’s a lack of emotion, a lack of connection,” she said. “It’s all about being pushed through the process — that’s how it felt.”

However, that could be because “hospitals are in the business of practicing medicine,” not recognizing birth for the “incredible experience” it is, Mendoza said. That’s where midwives and doulas can add something different to the birthing business.

Not all insurances will cover midwife care or home-births; sometimes they are considered “out of network” so payments will be higher. Certified professional midwives are not required to carry liability insurance, though. It is rare for a midwife to be sued, Childress said, partly because the practice relies on relationship-building and informed choice.

Childress believes the cost for midwife care is less than one would pay for hospital care, because there are not the accompanying hospital charges, which appear to escalate the cost of birth.

Community Outreach Manager Paul Mitchell said Columbia Memorial is interested in reducing the C-section rate and “they routinely evaluate cases and look for improvement opportunities.”

“At the end of the day, we would like to have all vaginal deliveries, as it is best for the mother and baby,” he said. “We weigh all of this with how best to provide a safe delivery for the individual mother.”

Prior to delivery, obstetricians, pediatricians and nursing staff review individual cases, Mitchell said. When a patient is admitted to the hospital, her risk factors “are evaluated by the entire team with an eye on both the mother’s and the baby’s well-being,” he added.

As for interventions, the hospital tries to use integrated therapies, such as aromatherapy, massage and guided imagery, to minimize medical interventions. They also encourage walking and provide a labor tub, he said.

“Our providers, nurses and all other hospital staff are committed to providing care in line with CMH’s Planetree philosophy, which boils down to providing care that supports the whole person,” Mitchell said. “Many of our returning mothers will request, by name, to be cared for by a nurse that they connected with during a previous birth.”

While childbirth in general poses potential risks to mothers and babies, regardless of the delivery method, the rapid C-section rate increase without evidence of direct causes “raises significant concern that cesarean delivery is overused,” states a research paper by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The trouble is, there is not the research to “tease out which ones really meet the threshold of risk versus benefits,” said Dr. Aaron Caughey, who is chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and associate dean for women’s health research and policy at the Oregon Health and Science University.

When considering safe and appropriate opportunities to prevent overuse of cesarean deliveries, sources suggested several methods.

While it would not lower the primary cesarean rate, which is most important, increasing local access to vaginal births after C-sections (VBAC) for appropriate patients could help break the cycle often created after a primary C-section.

Up until a few years ago, CMH and Providence Seaside Hospital had physicians who would conduct VBAC, but the hospitals both changed their policies. Providence’s decision was driven by the potential risks associated with such births and the limited resources of a small community hospital, McCoy said.

Among suitable candidates for VBAC, approximately 60 to 80 percent will have a successful vaginal delivery, according to the OB-GYN group.

The other 20 to 40 percent will end up needing another C-section, so the congress recommends hospitals have an anesthesiologist and obstetrician who can do surgery in the hospital at all times.

For small, rural hospitals that are under-resourced, having a team available in case a VBAC attempt turns into an emergency situation is sometimes not a viable option, especially with other hospitals an hour or two away, Caughey said.

Childress, and often other midwives, can conduct VBACs depending on patient risk assessment.

The use of doulas before and during the birth process seems to have positive benefits, as well. Doulas are individuals who offer emotional and mental support to women — and their partners — during birth. They are not medically trained, but “having someone by your side, who’s an advocate for the mom during the birth process” can be a great option, Childress said.

Using doulas in hospital settings has produced some positive results.

In a research paper by Dr. Ellen Hodnett and others in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews in 2013, 22 trials involving 15,288 patients revealed women given continuous support — such as that provided by a doula — were more likely to have a spontaneous vaginal birth; their labors were shorter; and they were less likely to have a C-section or instrumental vaginal birth or a baby with a low Apgar score, the standard method for testing a newborn’s health. The results were best when the continuous care providers were neither part of hospital staff nor in the women’s social network.

Group coordinated care also is a practice that’s been adopted by certain institutions, such as the Oregon Health & Science University’s Center for Women’s Health. Under that model, the prenatal care of women who share a similar due date is provided through discussion and support groups led by a midwife and nurse-midwife. Each of about seven sessions lasts nearly two hours.

Not only do group sessions help relieve some of the responsibility for prenatal care and education from physicians, who have numerous patients to see, but it creates an environment where multiple women and their partners feel free to ask questions and learn from one another, Mendoza said.

Women need to feel like they had input and a choice during every step of the way, she said. “We want women to feel like they’re heard,” and that birth didn’t “just happen” to them, she said.

Fairall agreed, adding, “a better birth outcome is not necessarily not having a cesarean.” Rather, a good outcome, she said, is when “you’re an active part of your health care.” For deliveries that require C-sections, she said, women should “feel they can embrace having had a cesarean because they knew what was going on.”