Partners work to finalize county deflection program

Published 8:40 pm Monday, August 26, 2024

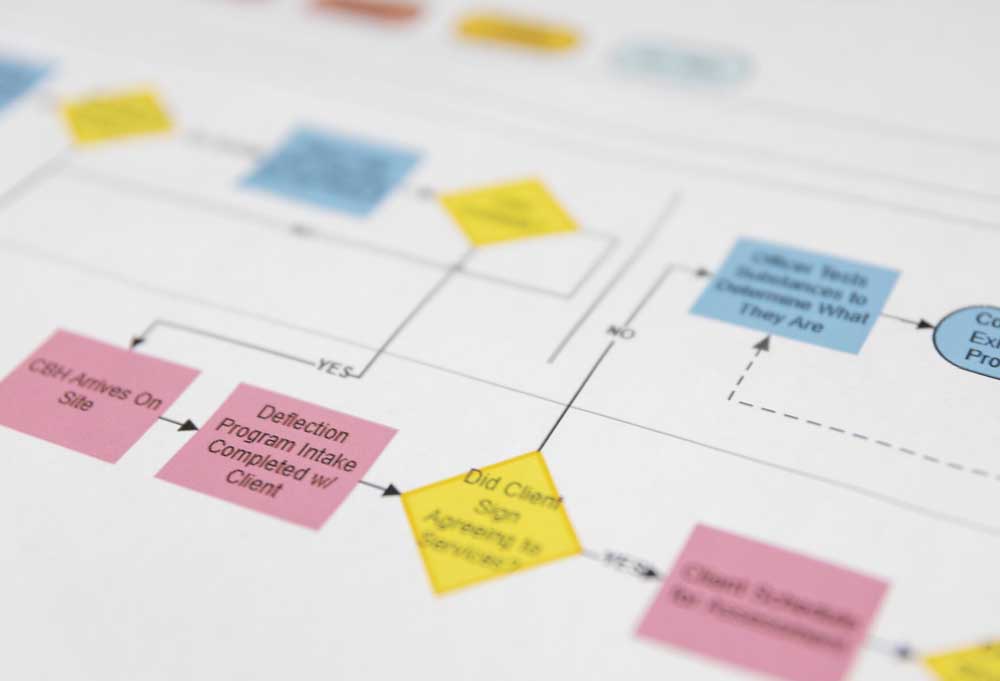

- A flow chart tracks Clatsop County’s deflection program for people cited for misdemeanor drug possession after Sept. 1.

As drug possession becomes a misdemeanor crime again in Oregon, leaders in Clatsop County are preparing to launch a program aimed at steering people away from jail and into treatment.

In 2020, Oregon voters approved Measure 110, which decriminalized the possession of small amounts of illicit drugs. This year, following what many considered an unsuccessful experiment with decriminalization, the Legislature rolled back portions of the law, allocating roughly $211 million for treatment and addiction services and more than $20 million for grant funding to support optional county deflection programs.

The idea behind deflection is to offer an alternative to the criminal consequences set to return on Sept. 1. In Clatsop County, representatives from law enforcement, the courts and Clatsop Behavioral Healthcare have spent the last four months developing a program ahead of the deadline — and generally, they seem optimistic about putting it into motion.

“I’m really hopeful for this project, because it feels like we all have the same goal, and that is to help people get the treatment they need,” said Amy Baker, the executive director of Clatsop Behavioral Healthcare, the county’s mental health and substance abuse treatment provider. “The criminal justice system has its place — it’s an important part of the system — but if we can not go that route and get somebody the help they need, it’s just better for everybody involved.”

Process

Under Measure 110, people found with small amounts of drugs would receive a citation and have the option to either pay a $100 fine or call a statewide hotline for a substance use disorder screening to have the charges dismissed. The Astorian reported last year that police officers and sheriff’s deputies on the North Coast issued relatively few citations for drug possession and that most people cited in Oregon failed to appear in court or take advantage of the screening option.

With recriminalization around the corner, the system will soon change.

Through the deflection program, a Clatsop County resident found with drugs can initially be written a deflection citation, rather than a criminal one. From there, the person will have 72 hours to make contact with Clatsop Behavioral Healthcare to engage in treatment.

Baker said the goal is to facilitate a “warm handoff” as often as possible — either by providing a ride to Clatsop Behavioral Healthcare’s Rapid Access Clinic on W. Bond Street in Astoria or by having a recovery ally meet the person on-site. That handoff can be critical in getting people connected with the resources they need, said Trista Boudon, the nonprofit’s recovery services program assistant manager.

Often, Boudon said, recovery can feel out of reach if a person is only interacting with law enforcement or attorneys. Recovery allies are nonauthoritative figures who have experienced addiction themselves and can walk with people through their recovery journeys.

“They have that lived experience of substance use and recovery,” Boudon said. “Some have that lived experience of substance use and law enforcement contact, understand that it is a chaotic, scary time, for lack of better words, for some folks, especially with the unknown, especially if these are folks that don’t have a history with the criminal justice system, could be first-time offenders, don’t know what to expect.”

A warm handoff can also make a difference for law enforcement officers, said Lt. Kristen Hanthorn, the county’s community corrections director.

“A lot of our officers and deputies really want to help people, and it’s gonna be a benefit to them to be able to know that this person is taken care of, and they can move on to the next call for service or the next thing that they need to do,” Hanthorn said.

Clatsop Behavioral Healthcare has six recovery allies and plans to hire one more to work specifically with deflection patients. The nonprofit has also designated a certified alcohol and drug counselor for the program. To complete the deflection program, a person must stay engaged in treatment for 45 to 90 days.

Treatment will be unique for each individual, but Baker said the focus will be on progress, rather than abstinence. If a person re-offends while actively engaged in treatment, they’ll remain in the deflection program.

“We don’t want to … hang this threat of a criminal charge over their head for six months or a year,” Hanthorn said. “It’s really a short time period for them to get engaged and start getting the services they need, and then make the decision, ‘OK, now we can dismiss and get rid of that original charge.’”

Accountability

While deflection offers an alternative to Circuit Court, the program doesn’t come without guardrails and consequences. Some people may not be good candidates for the program. Others may fail to contact Clatsop Behavioral Healthcare or stay engaged in treatment.

“There’s an accountability piece to this, right?” Boudon said. “It’s definitely not super, super stringent, but there are some pieces that have to be accomplished on the client and participant’s part in order for this to work out the way it’s all described. That’s that engagement piece, and following through with the instruction.”

If a person fails the deflection program or refuses treatment, they’ll be issued a criminal citation — but even then, there will be other offramps, like conditional discharge. If a person ends up in jail, they can also receive resources and counseling through the jail’s medication-assisted treatment program.

All of the services available to people through deflection are also available at Clatsop Behavioral Healthcare on a walk-in basis, but Baker hopes the program will open new doors to treatment and provide a pause for people that might not otherwise exist.

“I think it’s going to give us the opportunity to potentially reach a slightly different population of folks who haven’t been as ready or willing to engage in doing something different,” Baker said.

Rollout

Just because drug possession becomes illegal again on Sept. 1 doesn’t mean there will be an immediate influx of people being cited. Hanthorn said the deflection program will likely see a slow initial rollout. Overall, she feels the county is prepared.

Still, Sept. 1 is right around the corner, and the deflection work group has a to-do list to complete. Moving forward, they’ll be finalizing a procedure manual and developing a method for tracking people’s progress. The county’s newly hired deflection coordinator will also be working to develop training for law enforcement officers and help facilitate communication between law enforcement and Clatsop Behavioral Healthcare.

Lt. Guy Knight, of the Seaside Police Department, who serves on the deflection work group, said officers are generally prepared to enforce the new law on Sept. 1. Even if they aren’t familiar with how to write a deflection citation, the district attorney’s office can take criminal citations and refer people into the deflection program. As officers become more familiar with the program, the process will become more streamlined.

For newer officers, it may be the first time citing people for drug possession and directing them into treatment.

“It’s going to be a little bit of a learning curve for them,” Knight said. “But realistically, I think they’re all excited about the fact that now we have an actual tool, other than responding and writing a ticket, not knowing if there’s any kind of outcome or any kind of end game to how we’re going to fix the problem.”

When the referrals do start rolling in, Baker said Clatsop Behavioral Healthcare will be ready. In the past year, the nonprofit has expanded its staff and increased capacity through partnerships with other treatment providers. It’s also engaged in extensive internal conversations about deflection so everyone on the team knows what to expect.

Ultimately, Baker said the goal is to get people to help they need — whether it’s through a deflection citation or further down the line.

“We want them to succeed,” she said. “We don’t want to be the barrier. We want the only barrier to be whether or not they’re ready to do something about their substance use problem.”