Seen From Seaside: Gearhart author crosses the bar in a two-man kayak

Published 1:11 pm Monday, May 22, 2023

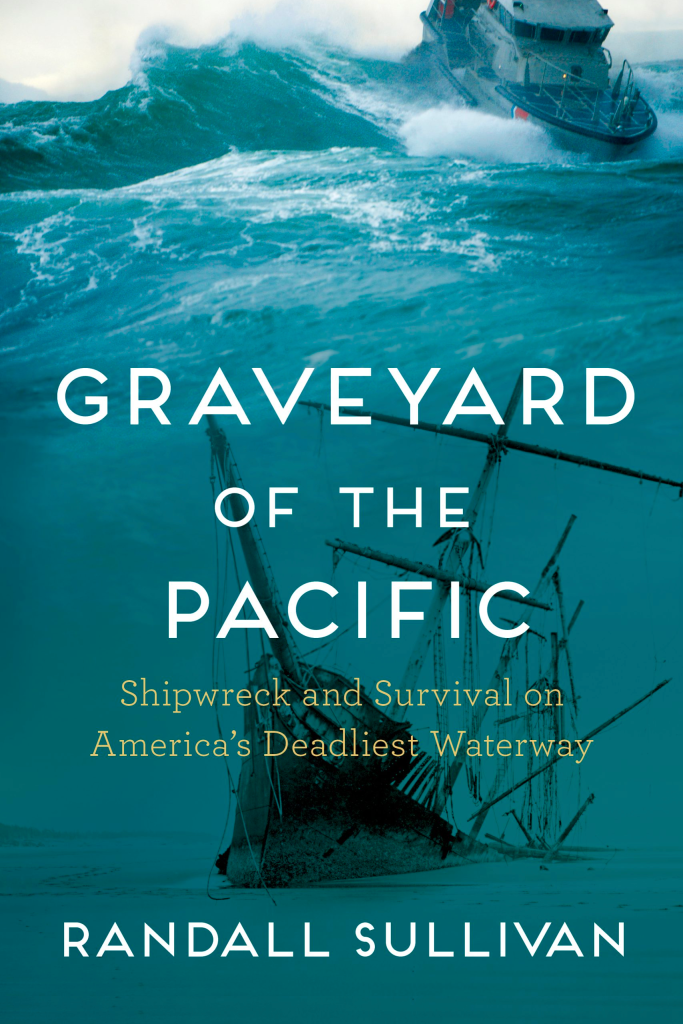

- Graveyard of the Pacific

Gearhart resident Randall Sullivan is well known for his decades at Rolling Stone and Esquire, including the article that provided the basis for “The Billionaire Boys Club.”

“LAbyrinth: A Detective Investigates the Murders of Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G., the Implication of Death Row Records’ Suge Knight, and the Origins of the Los Angeles Police Scandal.”

Sullivan’s reporting on the murders of Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. culminated in the book, “LAbyrinth: The True Story of City of Lies, the Murders of Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. and the Implication of the Los Angeles Police Department.” The book was made into the movie, “City of Lies,” starring Johnny Depp and Forest Whitaker.

His latest book, part history and part memoir, will hit home for local readers. At first glance a travel tale of crossing the Columbia River Bar in a two-man kayak, “Graveyard of the Pacific,” collects history, adventure and a stunningly personal memoir of fathers and sons.

What could put a man pushing 70 to challenge the most difficult straits anywhere?

“A deeper impulse was driving me,” Sullivan writes, “the wish for some unpronounceable rite of passage that could only happen in the later stages of life.”

The son of a longshore foreman, Sullivan was well acquainted with the rigors of the ocean.

Sullivan recruited experienced sailor Ray Thomas as his partner on the trip. Thomas advised Sullivan that the mouth of the Columbia was “the most challenging environment” for high sea rescues in the country.

The trimaran was a two-seater, 19 feet long by just a little more than 2 feet wide. The drive system consisted of two “kick-up fins” attached to pedals that could nearly double the boat’s speed when the sail was full.

In the course of Sullivan’s narrative, he pays homage to the shipwrecks of the past, the shipwrecks like the William and Ann in 1829, the Primrose, the Nisqually, the Dreadnaught and the most famous, the Peter Iredale “among the dozens of brigs, barques, scows, schooners and freighters” that had foundered in the Clatsop Spit.

“Even with newer and better charts in hand, however, one ship after another went down trying to cross the Columbia Bar,” Sullivan writes.

Four ships were wrecked in 1849 alone and another five sunk in 1852.

In 1913, three vessels were lost in the North Channel in a matter of three months.

Sullivan draws the characters and dynamics of the boats, their crew and their missions in historical context.

He provides an introduction for the general reader by putting you directly midships to the perils and tragedies of seamen throughout the 20th century, with a roster of the Andrada, the Laurel, the Columbia, the Triumph II and the Sea King.

U.S. Coast Guard Petty Officer Charles Sexton, gave his life to free injured crewmen as the ship sank beneath the waves, becoming an exemplar of valor to those who performed rescues on the bar.

With these tales of heroism, Sullivan intercuts his own story, a shocking one, of a father so severe and violent that a blow Randall received from his father as a child left him deaf in one ear.

Whippings from his father continued “month after month, year after year,” Sullivan wrote.

But Sullivan’s emotions were always conflicted. “I still loved him and needed him,” he wrote.

Their closest point of contact came from the stories that his father told of his days as a seaman.

“What they provided was something like tangible evidence that he had been, and so perhaps still could be, a better man, one who was funny and free and far from the agonies he knew ashore,” Sullivan writes.

Thomas, a successful trial lawyer as well as an expert sailor, carried a family history similar to Sullivan’s. “Ray had dealt with the pain and humiliation of such brutality at the hands of a father much as I had, by hiding it from others and denying it to himself.”

These experiences created a male bond and a mutual search for understanding. If 70-year-old men are still boys at heart, this adventure proved it.

Seated in the trimaran on July 16, 2021, amidst a “pandemonium of waves,” Sullivan writes, “I felt no fear, only anticipation.”

“Seated in the rear position, I could just see Ray’s back, until he swiveled to look at me over his right shoulder. ‘You and me, brother,’ he called. ‘Let’s live through this.’”

Time slows in what Sullivan imagines might be the last seconds of life. “We were swung like a tilt-a-whirl car on the crest of the wave, then plunged down sideways when it began to break.”