Seen from Seaside: Thinking vertically in the face of a tsunami

Published 11:15 am Thursday, September 5, 2019

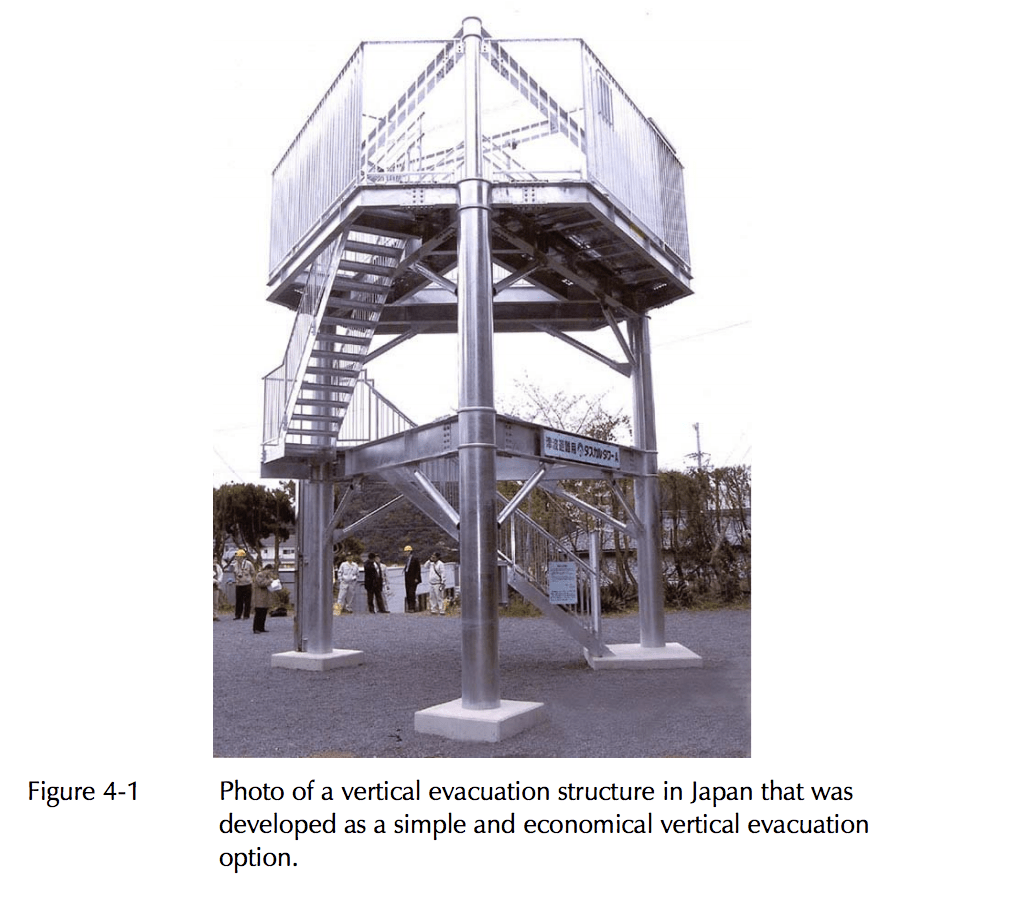

- Photo of a vertical evacuation structure in Japan that was developed as a simple and economical vertical evacuation option.

The world is watching as the Oregon Coast prepares to meet one of the nation’s most perilous threats, a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake and tsunami.

In late June, Gov. Kate Brown signed House Bill 3309, which amended previous law to no longer prohibit the construction of buildings such as hospitals, schools and other emergency preparedness centers in tsunami inundation zones along the Coast.

Among its sponsors was state Rep. David Gomberg, D-Otis.

“The central question is, with a one-third chance of a major event, do we abandon the coast, or do we prepare?” Gomberg told the Signal. “For most people here, their life savings and life debt are centered in their homes. Do we bankrupt people and tell them to walk away?”

The motivation for the change on the state level was, in part, to promote economic development in coastal cities and increase property values by having these essential facilities nearby, according to some lawmakers, said Rep. Tiffiny Mitchell, D-Astoria.

“This bill in no way encourages building in the tsunami inundation zone,” Mitchell said after her July Seaside town hall at the library. “Rather, because of the way things were before this bill was crafted, critical services within the tsunami inundation zone were unable to receive grants to retrofit for resiliency or even move out of the inundation zone.”

With the passage of the bill, she added, the intention is that people will continue to do the smart thing — not build in places that would be ill-advised. “The bill, however, does open the door to improvements in our processes, particularly for coastal regions.”

No place to run?

Writer Kathryn Schulz won a Pulitzer Prize for her coverage of Seaside’s efforts to move schools out of the tsunami zone.

After the Legislature’s vote in June, she blasted the decision in a new essay, again warning of the impact of the tsunami: “it will obliterate everything inside a skinny swath of coastline,” she wrote in the New Yorker, “700 miles long and up to three miles deep, from the northern border of California to southern Canada.”

Oregon’s bill “makes it perfectly legal to use public funds to place vulnerable populations — together with the people professionally charged with responding to emergencies and saving lives in one of the riskiest places on earth.”

But residents and coastal communities are clinging to the belief that their cities will be worth rebuilding.

“Communities that have spent millions of public dollars to shift fire or police stations inland are frustrated to find them potentially back inside the inundation zone,” the Register-Guard wrote in a June op-ed.

Vertical evacuation structures remain tantalizing, offering the promise of survival in the midst of ruin.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency first addressed the issue in 2009:

“A potential solution is vertical evacuation into the upper levels of structures designed to resist the effects of a tsunami. … to provide short-term protection during a high-risk tsunami event.”

These include buildings or “earthen mounds” with sufficient height to elevate evacuees above the level of tsunami inundation, and “designed and constructed with the strength and resiliency needed to resist the effects of tsunami waves.”

In “Up and Out 2,” published in 2014 by the Portland Urban Architecture Lab for the Oregon Office of Emergency Management, designers considered vertical evacuation berms, vertical evacuation towers and “tsunami ready” vertical evacuation towers “for significant at-risk populations, that will become a prominent city feature, holding important public institutions and emergency management operations.”

Cost, effectiveness at issue

But effective use and construction of vertical evacuation structures remains prohibitively expensive and design plans questionable.

A 50-foot-high tsunami could flood a building to its fourth floor, depending on ground elevation and height, Horning said.

“It could be possible to site hospitals and police several stories above ground in vertical evacuation structures, although equipment, such as police cars, might be swamped by inundation,” Horning said.

Designs are still in their infancy — and scientists don’t even know if they’ll work.

“It’s too early to tell if vertical evacuation on a large scale would be effective in a massive earthquake such as the one in Japan,” Harry Yeh, a professor of coastal engineering at Oregon State University told the American Society of Mechanical Engineers in 2011 after the Japan quake.

If the vertical evacuation structure is located near other buildings damaged during the earthquake, debris may block the entrance, the Federal Emergency Management Agency wrote in the 2009 document, “Vertical Evacuation From Tsunamis: A Guide for Community Officials.”

If a vertical evacuation structure serves another purpose, such as a community center or school, the building contents for those uses could impede access for those coming to use the facility.

Potential hazards include sources of large water-borne debris, sources of waterborne hazardous materials, and unstable land.

Some vertical evacuation structures may need to be located at sites that would be considered less than ideal, authors of the FEMA study wrote.

Costs deterred Cannon Beach in 2009 when architect Jay Raskin presented plans for a $4 million “tsunami resistant city hall,” Nancy McCarthy, a member of the Cannon Beach City Council and former editor of the Cannon Beach Gazette told the Signal.

If it had been built at the time it would have been the first vertical evacuation structure in the nation.

“They were thinking about building it on the same site where City Hall is now, and there was some concern that it was still too close to the ocean,” McCarthy said. “Not everything would necessarily pass through the space between the ground and the elevated first floor.”

The design showed an evacuation site on the roof, she added, but the question was how people would get there — it was feared that the stairs it would take to accommodate hundreds or even thousands of people would have to be massive, and disabled folks would have little or no access in time to be safe. And how many people would the roof hold anyway?

The cost also alarmed residents, McCarthy said.

The structure plan never went to a bond measure.

Future promise

Nevertheless the idea of safety above the tsunami line continues to prove tantalizing.

The vertical evacuation structure in Westport, Washington — built to hold 2,000 people — was completed in 2016 to coincide with the rebuilt Ocosta Elementary school, at a cost of $2 million.

Berms are cheaper — in 2011, the city of Long Beach priced a 40-foot high berm at $250,000.

Could a vertical evacuation structure be the answer in Gearhart, as officials seek a location for a new firehouse?

“I don’t think that would work for the heavy fire trucks of a fire department,” Horning said. “For a small town that has limited funds, building a vertical evacuation structure would probably be cost prohibitive.”

To meet an L-1 earthquake at 60 feet, Gearhart would need to have a fire station at its present site — about 24 feet above sea level — with service bays at least at 45 feet (high) to avoid water, or at least three stories above ground.

“How does one get a truck up there?” Horning asked.

“You’d need to spend huge amounts of money just to build a ramp. It would probably be 10 times as long as it is high, or around 200 feet in length. That’s a lot of concrete. You would need to piggyback it on some kind of commercial development, which is unlikely for Gearhart and nearly as unlikely for Seaside.”

According to geologist Tom Horning, one downtown building may already offer safety during a Cascadia event.

Horning, who studied vertical evacuation sites as a member of Seaside’s Tsunami Advisory Group and a consultant to the Gearhart Firehouse Committee, said in an interview the WorldMark resort parking garage might handle the quake and might be high enough to be above a 60-foot tsunami to have the two top levels available to the public.

“Probably a lot more room is available within the condo tower than the parking garage, so the business ought to have a public policy stating that they will accommodate everyone they can should the quake strike and the tsunami roll in,” Horning said. “We should be confident that the building could carry the loads and resist damage from both the quake and the wave.”