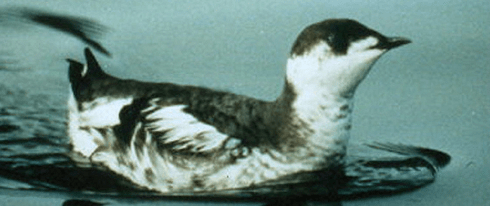

The marbled murrelet

Published 6:35 am Thursday, April 12, 2018

- The marbled murrelet.

When they are nesting, marbled murrelets stay silent and well hidden. In fact, the coastal seabirds remained a mystery from the time they were discovered in the 1700s by Capt. Cook until 1974, when the first nest was discovered in California.

“There was nothing known about the bird at the time, or at least white man thought,” said S. Kim Nelson, a research biologist with Oregon State University and the Oregon Department of Fisheries and Wildlife.

Nelson spoke at a “Listening to the Land” lecture sponsored by the Necanicum Watershed Council in Seaside March 21.

“The native Americans knew about the marbled murrelets, they knew where they nested,” Nelson said. “They knew about the beautiful dance they do in courtship where they put their bills up in the air and swim across the water and they dive under the water and come up together.”

But nobody thought to ask the Native Americans about the bird that nests deep in forests and forages for prey at the ocean’s edge.

“The Tlinget tribe revered the marbled murrelet. They wouldn’t eat the murrelet because they thought they were so special and mysterious,” Nelson said.

In the early 1900s, ornithologists still wondered where the murrelets nested. In the 1970s, the National Audubon Society offered $100 to the first person to find a marbled murrelet nest. That occurred in 1974 when a tree climber found a nest in a Douglas fir tree in California’s Big Basin Redwoods State Park.

It wasn’t until 1990 that the first nest in Oregon was discovered. There are about 70 known murrelet nests in Oregon, Nelson said.

Formerly listed as a “threatened” species, marbled murrelets recently were relisted as “endangered” in Washington, Oregon and California.

Although they can live for 15 to 20 years, they have a low reproductive rate, Nelson said. They don’t breed until they are 2 or 3 years old, and they don’t breed every year. When they do breed, they lay only one egg between April and July, and if that egg fails, they won’t always renest. They often return to the same forest stand during breeding season every year.

The birds, which fly between two ecosystems — forest, where they lay their eggs on large tree limbs, and marine environments, where they feed in shallow water — are experiencing a decline in the habitat they depend on for survival because the old-growth buffer they need is disappearing, Nelson said. As a result, 70 percent of nests fail annually, she added, and chicks aren’t surviving the fledge from the nests. If they do fledge, they aren’t surviving at sea until they’re old enough to breed.

One potential method of reversing the decline of failed nests could be preserving a larger buffer of trees between clear cuts and older forests where the birds nest, Nelson said. The larger buffer may prevent predator birds, such as stellar jays, American crows and common ravens from reaching the nests, she said.

Because murrelets are finding less suitable food in the ocean due to predators, over-fishing and warmer temperatures, Oregon’s five marine reserves will be “great” for the birds, she said. They will find prey in the reserves, which are either closed to fishing or allow only limited fishing. The reserves will be “nurseries for the fish,” she added.

“What murrelets need is dependable, abundant prey, right where their nest sites are,” Nelson said. “So they don’t have to fly up and down the coast; they can fly straight out from their nests and find their prey.”

The Cape Falcon Marine Reserve, near Oswald State Park, will support a known murrelet nest in the park, Nelson said.

“As the (marine reserves) are there longer and longer, we can look at the impact, and from what it’s shown so far, it can only be beneficial for the murrelets,” Nelson said.